The past year has probably been the most culturally and politically lively in sports in the last half-century. Protests, boycotts, activism and sit-outs have made regular news, and not only on the sports pages themselves. Athletes have made national headlines from the sidelines. But perhaps no single athlete’s claim on changing the world for the better has been as authentic as Laurent Duvernay-Tardif’s.

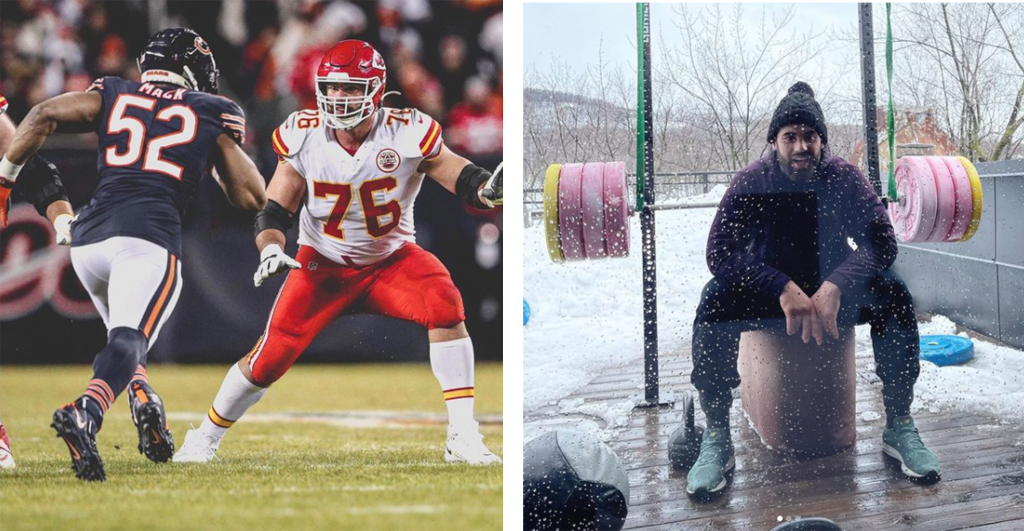

Duvernay-Tardif, who turned 30 in February, was a starting guard for the Kansas City Chiefs NFL football team from 2015 until the beginning of last season, during which he didn’t play at all. This was not because he was injured but because he chose not to. Duvernay-Tardif was one of numerous players in the NFL and other pro sports leagues who sat out the 2020 season for pandemic-related reasons, mostly out of health precautions (at least one athlete’s opt-out was accompanied by an explicit political statement).

Duvernay-Tardif stands apart from the others — far apart. He is, for one thing, one of the few Canadians (and even fewer Quebecois) playing in the NFL. And he’s one of even fewer doctors. Over the last few years, Duvernay-Tardif has been pursuing his medical training. He earned his M.D. in 2018 from McGill University and is currently a student in Harvard’s School of Public Health.

Here’s another way in which Duvernay-Tardif stands apart: He’s the rare athlete who conducts his public life by fully articulated values. Those values, not only his medical calling or a developing global health crisis, informed a remarkable choice he made last March, after he took off his football uniform for the season. He decided to don a pair of scrubs and turn himself into an essential worker on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Duvernay-Tardif’s values are firmly embedded in his literal foundation. The Laurent Duvernay-Tardif Foundation (officially Fondation LDT) was established in 2017 to “light the spark that will encourage children to value the integration of physical and artistic activities into their educational career,” according to the foundation’s vision statement. Fondation LDT “organizes turnkey events that encourage a balance among sports, arts, and studies,” mainly for students in fifth and sixth grade. The goal of its “multi-sport, multi-disciplinary days” is to “encourage children to cultivate a variety of passions.”

The foundation enumerates five core values: Curiosity, Balance, Passion, Perseverance, and Commitment. All five are evident in Duvernay-Tardif’s apparently abrupt but in fact well-grounded choices.

CURIOSITY

His team, the Chiefs, won the Super Bowl in February 2020. Duvernay-Tardif went on a vacation to Europe not long afterward. Just before he boarded his flight back home to Canada, he learned of a new two-week isolation period for returning travelers. En route, other passengers “were talking about how they were going to go back to work the next day,” Duvernay-Tardif told Sports Illustrated last year. “I wondered: Am I the only one who actually heard that? I asked, ‘Do you guys know that you’re supposed to stay at home for 14 days?’” Only Duvernay-Tardif seemed to possess the curiosity to fully take in what an isolation period really meant.

Within a few weeks, he began “to ask how I could help,” he told Sports Illustrated, and “reached out to the [Canadian] health ministry and public health authorities.” Also curiosity: What’s out there for me? What are my options as a medical professional? He learned that, because he had not yet completed his residency, he was not qualified to practice medicine.

PERSEVERANCE

Duvernay-Tardif wasn’t dissuaded. He kept looking for ways to contribute, and in April he discovered that “health ministry officials started a campaign to recruit healthcare professionals, especially students in medicine and nursing.” He signed up, enrolled in a COVID-safety crash course, and within days was assigned to a long-term care facility in Quebec “in more of a nursing role, helping relieve the workers who have already been in place.”

It makes sense that Duvernay-Tardif’s football position is guard: one of those legions of mostly unrecognized linemen whose role is to protect the quarterbacks and running backs who get most of the attention. It’s an essential but anonymous position. And it puts the player who holds it on the front line.

BALANCE

When he signed on as a medical worker, Duvernay-Tardif had made no decision about whether he would play the following football season. At the time, the future of football was only a notion, anyway, and a doubtful one at that. But after he had spent nine weeks in the long-term care facility, Laurent-Duvernay recognized that the NFL’s summer training camps were soon to get underway. He agonized over whether to play in 2020-21.

“Sport is really important; it’s a connective tissue for society,” he said last April. “But it is not an essential business.” Moreover, “in 2020, just by playing football I could potentially expose cities to COVID-19 and spread the virus. I believe I have a responsibility toward my community from a public-health perspective, and by playing, the risks would become more than just personal, more than simply about me. For my whole career, my two passions [medicine and football] had complemented each other and aligned with my convictions. In this particular season, though, they did not align.”

He weighed the risks. He weighed the importance of sports with the importance of the health of others. On that scale, the choice made itself. He decided to stay in the hospital and not play football in 2020-21.

COMMITMENT

The work Duvernay-Tardif was given to do was hardly the stuff of TV doctors: relieving tired staff, administering shots, changing diapers, and feeding patients unable to feed themselves: “an orderly-slash-nurse-slash-everything they want me to do,” as he put it.

Yet it was demanding and difficult in its own way.

“The first few days, because I had focused only on the medical tasks in front me, I only saw the negatives, all the steps required and how long it took to take them,” Duvernay-Tardif said. But his emotions caught up with him. After his shifts, he would go home and “burst into tears”—an extraordinary avowal for a male athlete to make—”asking things like, What’s the purpose of all this?”

Four weeks into his stint, there was a virus outbreak at the long-term care facility. Duvernay-Tardif’s supervisor called him in tears and told him to stay home.

Without hesitation, he told her: “You know what? I’m coming in.”

At the moment when he had every opportunity to bow out, he renewed his commitment.

PASSION

Soon, Duvernay-Tardif recognized “the subtle and yet significant importance” underlying the work he had signed himself up to do. He “came to realize that the people I met with never left their rooms, or saw their loved ones on anything other than a screen.” He was struck less by their ailments than by their loneliness, and he understood that “connection, real connection, became part of my job description, more important than drawing blood and putting in urine catheters and crushing up medicine.

“It changed my whole approach to medicine,” he concluded, “influencing how I’ll be as a doctor in the future.”

That sea change occurred for him because, rather than resisting emotions (which are, after all, rooted in our passion)—the tears that overcame him after shifts and his supervisor when she called him about the virus outbreak, and the loneliness he saw in the patients to whom he tended—Duvernay-Tardif allowed himself to respond to and be guided by those emotions. Indeed, those emotions engaged in an interplay with his other values: curiosity about himself and others; commitment to his work; balance between performing the necessary medical tasks and seeing the humanity of those to whom he ministered.

Duvernay-Tardif received much high-profile praise for his service, culminating in December when he was named one of Sports Illustrated’s five Sportspeople of the Year, each one an example of “The Activist Athlete,” as the magazine dubbed them. A few weeks later, his team, the Chiefs reached the Super Bowl again. This time, they lost, largely because of their inability to protect star quarterback Pat Mahomes. (who was named, along with Duvernay-Tardif, one of Sports Illustrated’s five Sportspeople of the Year for his own activist efforts off the field). Mahomes was chased, hurried, hit, and sacked all throughout the game because the Chiefs were without multiple starting offensive linemen, including Duvernay-Tardif, whose absence from football was once again conspicuous, painfully so. That, of course, reamplified the reason for his absence, and thus his presence in our cultural awareness.

He has not yet announced whether he’ll play football in 2021-22. In a moment when athletes have perhaps more power than ever to speak their minds and make positive change, here’s hoping that Duvernay-Tardif is willing and able to stay in both games, to make the most of the attention his sports stardom brings him, and to continue to run interference for the values that drive him.