Major professional sports around the world are dormant right now, but the timing of the shutdown differs widely among them. The NFL is in its offseason, and no games or related revenue were lost; the league’s major springtime event, the draft, went on as planned with easily implemented distancing adjustments. The NBA and NHL, whose regular seasons were interrupted midstream, are engaged in day-to-day tactical planning for the possibility of resuming play in some foreshortened way, even as they look ahead to a safety-conscious 2020-21 campaign.

The effects may have been felt most acutely by spring and summer sports. Major League Baseball was less than two weeks from its opening day, and the heart of the ATP tennis season set to commence soon, when both were stopped just before they started. It was as if the garden beds were all tilled and readied for sowing—and then no seeds could be planted.

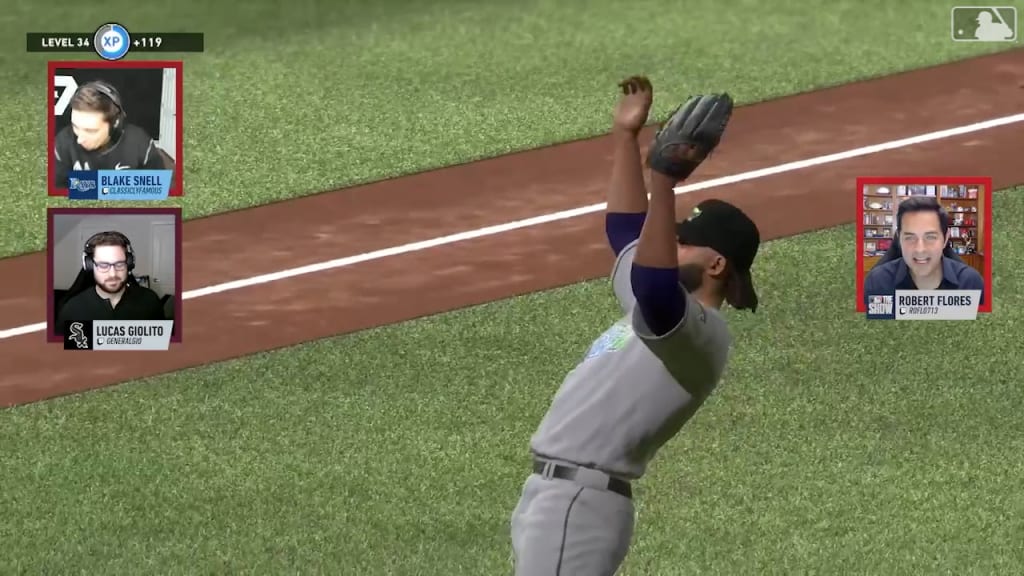

With the need for something to fill the airtime that was breathless for the arrival of these sports, both baseball and tennis have turned their attention to entirely invented action in place of the real thing: video game competitions. They’ve engaged some of their most recognizable players—as well as, in the ATP’s “Mario Tennis Tournament,” entertainment celebrities—in simulated showdowns streamed for fan viewing: fake games, in real time, with real players.

Some took the action quite seriously. Tampa Bay Rays pitcher Blake Snell, who was the American League Cy Young Award winner in 2018, also won the recent MLB The Show “Players League” championship trophy. Asked afterward about his triumph, Snell responded just as if he’d won a real, and really important, game.

“I was super confident going into it,” Snell said. “I really thought I was gonna win it, because of how much I play MLB The Show

After I lost the first game [of the best-of-three semifinal series], I thought, ‘Let’s lock this thing in.’ I just wanted to win. There was adrenaline. It was cool to feel the adrenaline.”

Tampa Bay Rays broadcaster Neil Solondz wasn’t surprised by the choice of Snell to represent the Rays, nor by his victory in the tournament: the choice was made at the intersection of sport and pastime.

“I’ve always known that Blake’s a huge video game player. Players on our roster [agreed], ‘If anyone’s gonna do it on our team, it should be Blake.’”

Both the baseball and tennis tournaments raised money for charity, but even that goodwill may not have been their greatest benefit. Maintaining a connection with fans is critically important for sports whose early-season action has been stilled. And this isn’t only about the games and teams. The pandemic also affects the entire communications apparatus around them: sportscasters and sportswriters; talk shows and advertisements; and everyone whose business is the dissemination, analysis, and coloring of the action and culture of sports. Without stories unfolding naturally on courts and fields, storytellers have to look elsewhere.

Solondz is finding that this unexpected challenge is broadening his vision and deepening his attention. For one thing, he has increased the hours he spends teaching himself Spanish, a longtime self-directed study aimed at better connecting him to baseball’s large Latino demographic. (More than a quarter of MLB players are Latino.)

For another, he has more time for what he calls “inspirational reading,” which involves both sports and non-sports books, from Mitch Albom’s classic Tuesdays with Morrie to Michael J. Fox’s autobiography, Lucky Man. Books like these are timely, according to Solondz: “Sports is about the human triumph—triumph and positivity in the face of adversity. We’re all looking for that right now.”

But his reading isn’t only about boosting morale and “keeping your mind right,” as Solondz puts it. It’s about enriching the essential practice of his work as a storyteller. “Any job is about constantly trying to improve,” he says. “And in mine, if you’re not learning to better tell stories, then you’re not going to have the success you want.”

With no games to call and analyze, and no pre- and postgame interviews to conduct, Solondz has instead been scheduling and posting a series of interviews with Tampa Bay Rays players past and present, deepening his knowledge of the team’s history. Meanwhile, he has kept to his assiduous scouting research of the Rays’ opponents in case the season should get underway later this summer. The shutdown gives him “a chance to do more homework, and all kinds of prep you wouldn’t get to do” during a normal season. And he is keeping his game-calling chops sharp by doing television rebroadcasts, five times a week, of ballgames from previous years.

“The act of storytelling is partly gathering information you think will be useful later,” Solondz says. “I don’t know that that necessarily changes [during the pandemic]. Perspective is knowing where you came from and where you’re going; but it’s also a context.”

And from that context comes fresh content.

“I think people appreciate new content. Some like nostalgia, especially in baseball, but there’s something about having something new, something fresh, that maybe educates them for a moment and also helps them escape everything that’s going on.”

The effort to keep creating that content keeps him “as engaged on Twitter as I would be during the regular season—maybe even more so. Putting together these interviews [with ballplayers] is helping me find some human aspect that fans can relate to. I have an opportunity to ask questions I think fans would want to ask,” for which there is generally less opportunity during the relentless grind of MLB’s 162-game season.

“It also helps me educate myself, so that when games return I have more to help me connect with fans. There’s a lot of stuff that I hope is sticking in the back of my mind.”

Perhaps there’s some stuff sticking in the back of MLB’s, as well. “I don’t know how much response MLB thought they might get to the Players League,” Solondz says, but the simulated video tournament was a surprisingly successful piece of ad hoc programming. In it, both Solondz and its inaugural champion, Snell, detected possibilities for the future—a future that could go beyond merely resuming baseball as we knew it and might make headway in expanding the sport’s scope and popularity. Happy as he was to have won the tournament, Snell said the best part of the experience may have been “the fan interactions, and how much they supported the players they were cheering for.”

Those interactions, Solondz notes, owed quite a bit to the Players League tournament’s programming structure itself.

“I thought it did a great job of bringing the personalities of the players to life,” he says. “For the younger fan, it melded old school and new school.” Solondz recalls hearing stories during his youth of the Brooklyn Dodgers of yore: “[Many of] the players lived near the ballpark, in the same neighborhood with their fans, and they’d see them on a daily basis.” To an extent, putting the gaming players onscreen accomplished a similar intimacy, allowing fans to see them not just as athletes but also as people, at ease in their easy chairs, hanging out in an open game room where fans could hang out, too.

Audience connection and cultivation is a significant issue in baseball, a sport which has perceived itself, especially over the last decade or so, as losing its traditional (and now aging) fan base, while failing to appeal to a younger demographic—even though, as Solondz noted, MLB is currently in a golden age of great players still in their mid-twenties: just the kind of ascendant young athletes to whom young fans ought to be able to relate naturally. Perhaps more Players League tournaments could help attract the more youthful audience MLB has been so desperately—and ineffectively—trying to build over the last decade or so. Ironically, a step in that direction seems to have come precisely when there is no actual baseball being played: take the game off the field, and attention instinctively turns to the people in the stands—and, perhaps more importantly, to imagining the people who could be.

Player and broadcaster alike see great potential here. Snell advocated for reviving the tournament during baseball’s formal wintertime hiatus.

“I think it would succeed even more in the offseason. People get bored and it gets darker a lot sooner, and they’ve got nothing to do outside the house, just like right now. I think [the shutdown] is something that’s exciting for baseball, because we’re learning a lot of things we can do when we don’t have baseball.”

Solondz agrees. “It may happen organically,” he speculates. “How Major League Baseball frames it, how they adapt—I think that’s part of the story. And I’m looking forward to helping tell that story.”